Those who pay attention to interest rates and the monetary policy of the South African Reserve Bank may be questioning the efficacy of the central bank. Should the bank be targeting inflation through interest rate policy? Should the bank be more intertwined with the South African government? Is there something more that the bank could be doing to positively affect the South African economy? These are some of the questions that may arise if you pay attention to markets and the economy. But to answer these questions we need to first understand the South African Reserve Bank and its history, saving opinions for a later stage. This short essay sets up a foundation upon which we can base further research and knowledge acquisition.

1. The Need For a Central Bank

Before the establishment of the South African Reserve Bank, the banking system in South Africa operated under a decentralised model where commercial banks issued their own promissory notes to the public, which were redeemable for gold. This was the gold standard period where different currencies such as the British pound, the U.S. dollar, the South African pound, the German mark, the Russian ruble, the Austro-Hungarian Krone, among other currencies, were backed by gold. Each bank note had to be backed by a certain amount of gold, which meant that banks needed to maintain significant gold reserves.

When World War I broke out in 1914, this led to volatility in financial markets, leading to a spike in gold prices globally, which made it increasingly problematic for banks to maintain their promissory exchanges with customers as countries needed to finance war expenses.

At this time the British and South African economies were tightly linked. Gold prices in Britain rose to a higher rate than they were in South Africa. Traders started acting on this arbitrage and would convert their notes to gold in South Africa, then sell that gold in Britain for a higher rate. As the demand for gold in South Africa grew, banks in South Africa were forced to buy gold at higher rates outside of the country for import into South Africa to satisfy this growing demand. This led to liquidity issues for South African banks and in response to these challenges, the commercial banks lobbied the government for relief from the obligation to convert banknotes into gold on demand. This culminated in the Gold Conference of 1919.

2. The Birth of the South African Reserve Bank

The Gold Conference in 1919 was held to address the financial instability faced by South African banks during and after World War I. The conference resulted in recommendations for a uniform banking act that would include stringent provisions against inflation and the establishment of a central bank to stabilise the currency and manage gold reserves.

Following the Gold Conference, the Currency and Banking Act of 1920 was introduced, which established the South African Reserve Bank (SARB). The Act determined that the SARB would 1) issue banknotes and manage the country's gold reserves - centralising control over monetary policy; and 2) to protect the SARB from the issues faced by commercial banks, the Act allowed for a temporary suspension of the convertibility of banknotes into gold, and at the same time the South African government put a hold on gold exports - thereby alleviating immediate financial pressures. The SARB officially opened its doors in June 1921.

3. The Great Depression

The official currency of South Africa during this period was the South African pound, tied at 1-to-1 with the British pound sterling. In 1922 the SARB officially started issuing notes to consumers, and in 1925 the gold standard was reinstated in South Africa. As the Great Depression, which began in 1929, started to affect global economies and markets, Britain decided to go off of the gold standard in 1931, however the SARB decided not to implement the same policies and kept the gold standard for the South African pound.

As volatility in financial (mainly gold) markets continued to heat up, South Africa experienced large capital outflows, largely due to falling investor confidence at the South African economy being able to maintain the gold-backed currency. The SARB sold a large volume of its gold reserves to try to defend the local currency. However a fresh wave of capital outflows hit the South African economy, culminating in a proclamation by the local government to end the convertibility of South African banknotes into gold.

4. Exchange Rate Systems and the Introduction of the Rand

Fast forward to 1944, the Bretton Woods Conference that year established a system of stable but adjustable exchange rates, overseen by the newly created International Monetary Fund (IMF). Under this system, currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar, which was convertible to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce. This arrangement allowed for controlled devaluations or revaluations of currencies under specific conditions to maintain economic stability.

At this time, the South African pound (SA£) was still pegged at a 1-to-1 ratio with the British pound (£), which was valued at $4.03 per £1. In 1949, the British government devalued the pound from $4.03 to $2.80, and since the South African pound was linked to the British pound, the South African Reserve Bank followed this devaluation.

In the mid-1950s, the Decimal Coinage Commission was established in South Africa to explore transitioning from the traditional British-style currency system (pounds, shillings, and pence) to a decimal-based system. In 1958, the Commission published a report recommending that the new currency be based on 100 cents per unit, with 1 rand (R1) equaling 10 shillings (or half a pound).

Coinciding with South Africa becoming a republic in 1961, severing its last constitutional ties with Britain, the rand (R) was officially introduced as the country’s new currency. The name “rand” was derived from the Witwatersrand, a ridge in South Africa known for its rich gold deposits. At the time of introduction, the exchange rate was set at £1 = R2.00, maintaining the previous value of the South African pound. The initial rand currency included coins in ½, 1, 2½, 5, 10, 20, and 50-cent denominations, and banknotes in rand denominations.

5. The Rand in a Global Context

During the 1960s there was a wave of global inflation largely caused by United States government spending towards the Vietnam war, while the Federal Reserve Bank maintained a policy of low interest rates to spur demand and spending. During this period, South Africa had exchange controls in place on non-residents, meaning there were limitations on non-residents repatriating investments and converting local currency into foreign currency. These controls were managed through a dual-rand system which separated the commercial rand (used for trade transactions) from the financial rand (used for capital transactions by non-residents). The South African Reserve Bank oversaw these regulations, which required that all foreign exchange earned by residents be sold at a predetermined rate to the central bank, thereby controlling how foreign currency was utilised.

Reasserting its independence from the British empire, in 1968 the British Government devalued its currency by 14.3%, but on this occasion the South African Reserve Bank decided not to follow with a similar devaluation. This implies the South African Rand appreciated vs the British pound.

As the Vietnam War continued to heat up, the United States found themselves introducing more “paper valued” money into the economy to finance war expenses, making it difficult to maintain the gold standard. In 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon announced that the United States would suspend the dollar’s convertibility into gold, effectively ending the Bretton Woods gold standard system. Following this decision, major industrialised economies (United States, the UK, France, West Germany, and Japan, among others) gradually transitioned to a floating exchange rate system, allowing market forces to determine currency values instead of maintaining fixed exchange rates.

Following Nixon’s announcement ending the dollar’s convertibility to gold, the South African Reserve Bank devalued the rand, setting it at approximately 71.29 cents per U.S. dollar. In response to global currency fluctuations, South Africa initially pegged the rand to the U.S. dollar, then shifted to the British pound, back to the U.S. dollar, then to a basket of currencies, and later returned to a U.S. dollar peg by the late 1970s. By 1978, the rand’s exchange rate stood at approximately 86.95 cents per U.S. dollar.

6. The Rand at the Height of Apartheid-Related Pressures

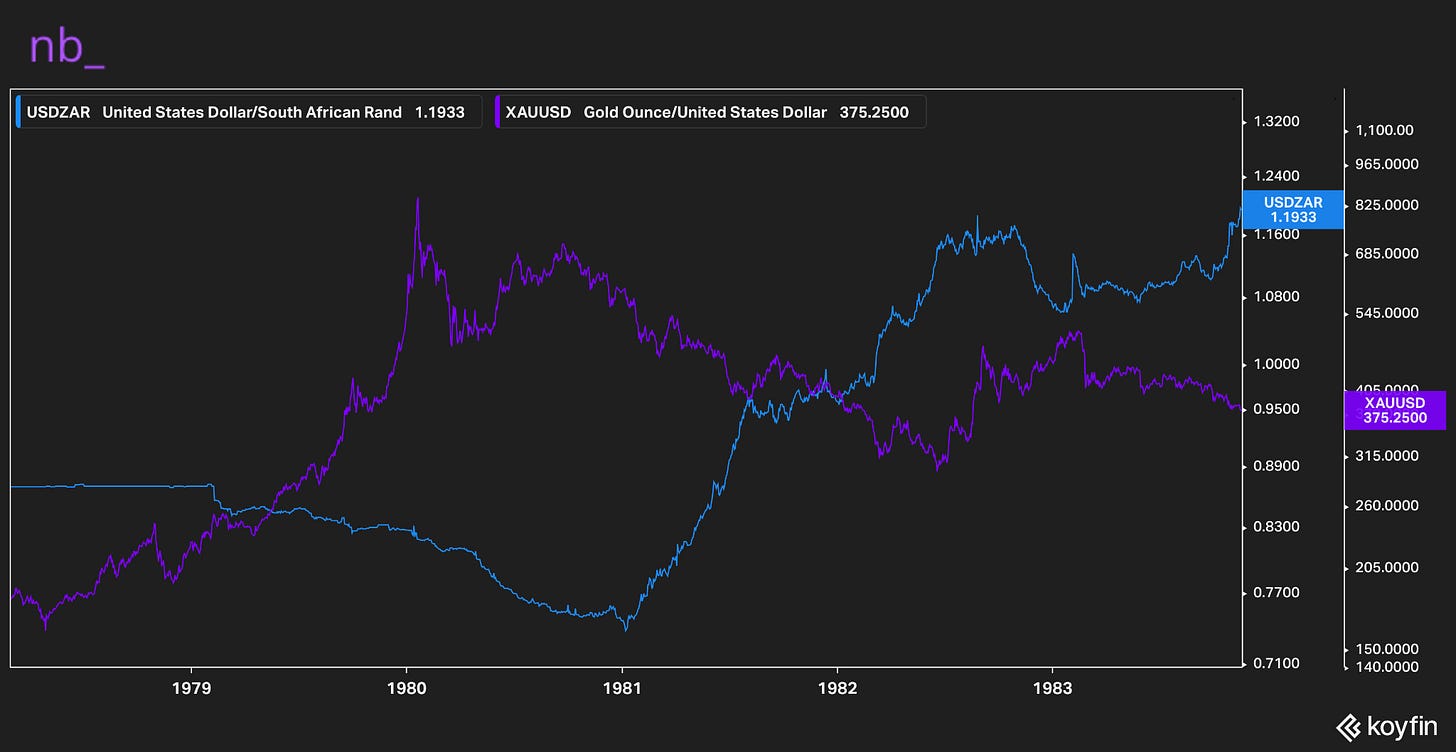

In the mid to late 1970s, South African exports surged as the country experienced a gold export boom, driven by a sharp rise in global gold prices. By January 1980, gold peaked at approximately $850 an ounce, fuelled by global inflation, economic uncertainty, and increased investor demand for safe-haven assets. However, this surge was short-lived, and by mid-1982, gold prices had plummeted to around $300 an ounce, dealing a significant blow to South Africa’s economy, which was heavily dependent on gold exports.

As the price of gold declined, so did the value of the South African rand, depreciating to R1.19 per U.S. dollar. The SARB was responsible for maintaining financial stability and managing monetary policy, however, its ability to act independently was constrained by government directives, particularly in maintaining the dual exchange rate system.

In 1983, the South African government, in an attempt to liberalise financial markets, instructed the SARB to abolished the financial rand system. However, the decision failed to restore investor confidence, as political instability - marked by increasing protests and riots against apartheid - continued to weaken the economic outlook.

By the mid-1980s, the economic crisis deepened. The SARB, as the lender of last resort, was tasked with intervening in currency markets to manage capital outflows and stabilise the rand. However, as foreign banks withdrew credit lines in 1985, South African authorities, under government orders, were forced to temporarily close foreign exchange markets and reinstate exchange controls for non-residents. The SARB played a central role in implementing these emergency measures, attempting to curb capital flight and slow the rand's depreciation.

Meanwhile, international pressure to end apartheid intensified. Sanctions from multiple nations globally led to further capital outflows, isolating South Africa from global financial markets. Despite the SARB's interventions, the rand plummeted from approximately 75.7 cents per dollar, to R2.91 per U.S. dollar by 1986, reflecting the severe economic distress.

Ultimately, the South African Reserve Bank found itself caught between executing government mandates and attempting to uphold financial stability in an increasingly fragile economic environment. Its role during this period was characterised by foreign exchange interventions, capital controls, and liquidity support, though these measures were insufficient to counteract the broader structural and political challenges facing the country.

7. The Role of the South African Reserve Bank Post 1994 Democracy

Between 1990 and 2000, the South African rand depreciated from R2.53/$1 to R7.62/$1, a period of economic transition as South Africa reintegrated into global markets following its first democratic elections and the end of apartheid. This decade saw significant economic reforms, including the gradual lifting of capital controls and movement toward a more open financial system.

During this time, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) transitioned from an exchange rate and capital control-focused mandate to a monetary policy-driven approach. In 1996, the SARB’s independence was formally enshrined in the Constitution of South Africa, which mandated that it protect the value of the currency in the interest of balanced and sustainable economic growth, in coordination with the Minister of Finance.

By 2000, the SARB officially adopted an inflation-targeting framework, setting an inflation target of 3% to 6% to promote economic stability and sustainable growth. Since the 1980s, the SARB’s role has evolved significantly - from focusing on currency controls and exchange rate management to prioritising price stability, financial stability, and systemic risk oversight across South Africa’s financial system. Today, the SARB functions as a modern, independent central bank, aligning with international best practices in monetary policy and financial regulation.

Summary

Before the existence of the South African Reserve Bank (SARB), South Africa had a decentralised banking system where commercial banks issued their own promissory notes backed by gold, but financial instability during World War I led to liquidity issues, prompting calls for a central bank.

The Gold Conference of 1919 led to the Currency and Banking Act of 1920, establishing the SARB to centralise monetary policy, issue banknotes, and stabilise the financial system.

Around the Great Depression, the SARB initially maintained the gold standard after Britain abandoned it in 1931, leading to capital outflows and currency instability, forcing South Africa to suspend banknote convertibility into gold.

South Africa’s currency was tied to the British pound until 1961, when the rand (R) replaced the South African pound, maintaining parity but aligning with global currency shifts.

Following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, the SARB adjusted exchange rate policies, devaluing the rand and experimenting with multiple pegs before adopting a basket of currencies approach, then a free-floating approach.

Due to economic instability caused by apartheid-related pressures, a gold price collapse, and international sanctions; South Africa experience a severe currency depreciation, forcing the SARB to reinstate exchange controls in 1985 to manage capital outflows.

Post-1994 democracy, the SARB transitioned to monetary policy-driven governance, adopting an inflation-targeting framework in 2000, ensuring price stability and aligning with global central banking standards.