To Investors,

On April 2nd President Trump announced a wide range of tariffs on goods imported into the United States. This day was called “Liberation Day”. But you might wonder: ‘liberation from what? The United States of America is not a slave to anyone, or constrained by anything?’ Today I want to explain Liberation Day, break down what all of these tariffs mean, how we got here, and to highlight the hypocrisy which a lot of countries have fallen into by screaming “bloody murder” about tariffs.

What happened on “Liberation Day” April 2nd, 2025?

President Trump announced:

A baseline 10% tariff on all goods imported into the U.S., effective from April 5, 2025.

Reciprocal tariffs on about 90 nations, with rates varying (e.g., 34% for China, 20% for the EU), effective from April 9, 2025.

A 25% tariff on vehicles and auto parts imported into the U.S., effective from April 3, 2025.

Continued enforcement of existing steel and aluminium tariffs, with some exemptions for Canada and Mexico.

Firstly the reciprocal tariffs are self-explanatory: the U.S. will impose the same tariff that any country has against the U.S. Here’s a chart shared by John Caple on X, which shows the tariffs countries currently have in place against goods imported from the U.S. The chart also shows the level of reciprocal tariffs (before the current Trump tariffs) that the U.S. has on those countries–and its zero.

The reason for the tariffs announced, according to President Trump and various members of his cabinet, is to reduce the United States trade deficit which has reached record levels of around $123 billion as of February 2025. Reducing the trade deficit is a piece of a larger three point plan where President Trump is trying to broadly improve the financial status of the United States by 1) reducing national debt for the U.S. which has ballooned to 123% of GDP as of 2024; 2) cutting government waste plus spending which is largely financed through government bonds at uncomfortably high interest rates of around 4-5% (this is where DOGE comes in); and 3) reviving the United States’s manufacturing and export economy.

Without going off on a tangent, U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent explained the idea well, I'm paraphrasing: the aim is to cut government spending by reducing the size of the government and related labour. When that happens, because government spending will be lower, the government won’t have to rely as much on debt-fuelled spending–so bond yields will go down. At the same time the government will generate higher revenues from tariffs and additional business that the U.S. will attract from tariffs. Again the government will rely less on debt spending because there will be more revenues to spend from. This will also push bond yields lower because the government will be in a better financial position from both higher revenues and less spending. When tariffs kick in and manufacturing productivity is brought back into the U.S., jobs removed from the government sector will shift onto the private sector and service the additional productivity growth.

But today we’ll mostly focus on how the Liberation Day tariffs play a role in that three point plan. Tariffs are a tax on consumption and in service of the larger mission these tariffs will make imports costlier while encouraging domestic production and promoting job creation in manufacturing by incentivising companies to produce in the U.S.

How Did We Get Here?

This strategy is part of Trump's "America First" mission–centred around highlighting that what school has taught us about how global trade is free, is inaccurate, and focusing on how because the United States is a disproportionate buyer of goods from every country, the U.S. is running costly trade deficits. The way that we got here is a mix of factors but my thinking is that after Nixon announced in 1971 that U.S. dollars would no longer be exchangeable for gold, the U.S. dollar started appreciating against global currencies because of the demand for the dollar. This meant that it became cheaper for the U.S. to import goods than it was to export goods and this led to a higher standard of living in the U.S. That, along with China entering the world trade organisation, along with other Asian countries, made U.S. manufacturing expensive because goods could be manufactured cheaply outside of the U.S. Deals were likely cut for the U.S. to run trade deficits with China, and the rest of the developing nations to prop up their economies. But this gutted the U.S. industrial base.

Here’s a quick story about the car manufacturing economy in the United States: Detroit, once the world’s car-making king, started cracking in the ‘70s as Japan’s cheap, efficient imports rolled in, and by 2001, China piled on with low-cost parts and vehicles—pushing the trade deficit to $213 billion by 2018 according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Jobs vanished, either to automation or overseas. Years later General Motors was forced to shut down its Lordstown, Ohio, plant in 2019, leaving thousands high and dry as production shifted to Mexico and beyond.

Nowadays many electronics are manufactured in Asia, and for the U.S., this led to 3.7 million jobs lost when this productivity shifted out of America. Textiles saw a 30.4% drop in Black manufacturing jobs from 1998 to 2020, chased overseas by cheaper labor according to the Economic Policy Institute. U.S. steel has been hammered too, with imports forcing plant closures according to a report from the American Iron and Steel Institute.

The hollowing out of the manufacturing sector switched the U.S. economy into a services based economy with manufacturing jobs replaced by services sector jobs. In general this resulted in a higher standard of living in the U.S., however when the standard of living improved in the U.S., the country had a higher consumption rate but a low savings rate, forcing the economy to issue foreign debt in order to support government spending.

As the dollar became stronger, this cycle continued to grow and grow, and has now reached unsustainable levels.

The high national debt and persistent trade deficit are reinforcing each other. U.S. national debt is high because the U.S. has a persistent trade deficit, and the persistent trade deficit means the U.S. must continue to fund domestic spending by issuing government bonds, but those bonds are issued at higher and higher interest rates so that makes the interest payments high, which means the government must continue to issue more government debt, which will continue to be at higher rates because, among other factors, the trade deficit is persistent.

Brief History of U.S. Tariffs

The Trump administration has chosen tariffs as the fix for this problem.

But tariffs aren’t an invention of Donald Trump and his cabinet. The United States has historically relied on tariffs to fund tax revenue and protect domestic industries.

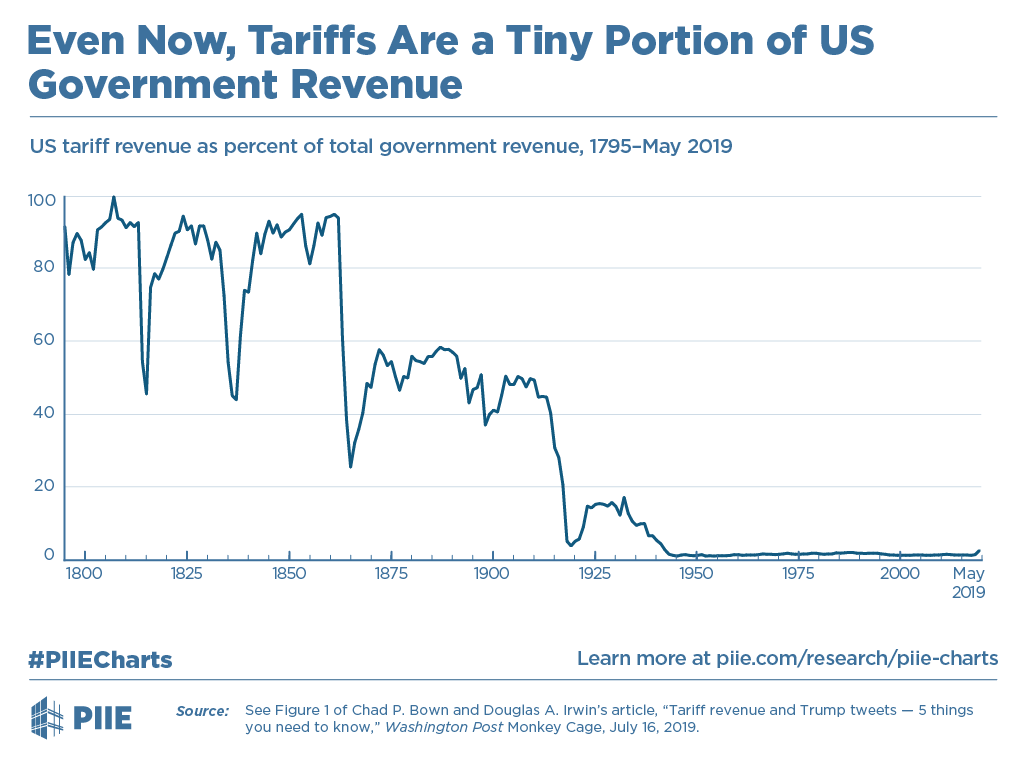

According to research by Anthony Pompliano, the United States never used to have income tax and relied only on tariff revenue. Pomp mentions that “George Washington signed tariffs into law as the second bill of his administration as the first President of the United States. A year later, the US Revenue Cutter Service (which later became the US Coast Guard) was created to collect [a] 5% tariff on all imports to the country.

Tariffs continued to be the main source of government revenue for about 70 years. These tariffs also protected American industries from foreign competition and ensured America was able to become self-sufficient, which was considered a national security issue at the time.”

This practice was eroded over the years however, and the chart below shows that tariff revenue for the United States is now effectively zero in comparison to the late 1700s.

Addressing Common Misconceptions

I’ve seen a lot of comments on social media about how these tariffs are “alienating” the United States and some friends of mine have also commented similarly in private conversations. I’ve also seen comments about how tariffs will lead to inflation so I want to address these inaccuracies:

The Trump administration is not alienating the U.S., instead they are trying to revert to more fair trade for the U.S. by reorganising the global trade order.

Tariffs will not lead to higher prices in the long term.

1. Is Trump alienating the U.S. from the rest of the world?

No. Here’s why…

As mentioned earlier in this letter, the U.S. is a buyer of goods from every economy in the world, which has led to the U.S. having trade deficits with those countries. We can all understand that selling more than you consume will put you in a better financial position, so trade deficits are bad—especially if they exist across the board and are growing persistently as shown in the chart below.

The U.S. therefore needs to take a stance that puts their country first and supports their local economy. The customer almost always has the leverage, so in this example as the customer to the world, the U.S. has leverage through tariffs because if you no longer have a customer you no longer have a business. Do you see where I’m going with this?

That said, there are many examples of countries that have similar protectionist policies and everyone is conveniently ignoring those because people are paying too much attention to the mainstream media which constantly distorts the truth.

Let’s run through a few examples…

India

India is known for its protectionist trade policies, particularly in the automotive sector. India reportedly imposes tariffs on imported cars at around 106% as part of a “Make in India” campaign to boost local manufacturing. This tariff doubles the price of imported cars, and therefore encourages consumers to buy domestically produced cars.

Additionally, ownership laws for foreign companies in India add another layer of protectionism. Foreign direct investment (FDI) is regulated, with certain sectors requiring joint ventures or partnerships with local companies. For instance, until recent reforms, the automotive sector often required foreign firms to collaborate with Indian partners, but restrictions remained in strategic sectors like defense and telecommunications.

China

China is an interesting and well documented example of a country that has intense tariffs and trade barriers. Historically, foreign carmakers were required to form joint ventures with Chinese companies to produce and sell vehicles, a policy in place until 2022 when China announced it would allow 100% foreign ownership in some cases. However, restrictions persist in strategic sectors like energy, mining, banking, insurance, and defense, where foreign ownership is limited to protect domestic industries.

Google, Meta’s social media products, and various non-Chinese shows cannot be accessed in China, which is no secret, and something the country is proud of. The difficulty for foreign businesses is also compounded by a complex regulatory environment. For example, intellectual property rights protection remains a concern, with reports of mandatory technology transfers in joint ventures. These policies apparently aim to foster domestic innovation but are controversial, with foreign companies often citing barriers to market entry and competition with state-backed enterprises. We also can’t forget that every industry is essentially state backed in China and is wholly supported through subsidised loans and policy.

And one other thing, while most of the world has a free floating exchange rate, China manipulates its currency by tightly managing its exchange rate with the U.S. dollar daily to reduce the impacts of currency volatility on their domestic economy. Where’s all the outcry about that?

Did you also know that China has tight capital controls to restrict capital flight in times of economic volatility?

South Africa

South Africa also has a tariff structure designed to protect local industries, with an average tariff rate of 7.1%, though specific goods like apparel face higher rates, such as 40% for finished goods. The tariff schedule, governed by the South African Revenue Service (SARS), includes various rates ranging from 0 to 30% but can be much higher in some instances. According to the International Trade Administration “the end rate for apparel is 40 percent, yarns 15 percent; fabrics 22 percent; finished goods 30 percent; and fibers, 7.5 percent. Import duties on vehicles and automotive components will remain at 25 percent on light vehicles and 20 percent on original equipment components through 2035.”

South Africans are also very aware of the ownership laws affecting local companies as well as foreign companies in relation to the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (B-BBEE) – which mandates companies to meet thresholds of black ownership and management control to participate in government tenders and contracts. This policy, while aimed at economic transformation, can pose challenges for foreign firms.

Ireland

As a member of the European Union, Ireland applies EU tariffs, with duty rates on manufactured goods from the United States generally ranging from 5-8%, based on the c.i.f. value at the port of entry. Agricultural and food items are subject to import levies that vary with world market prices, reflecting EU protectionism in these sectors.

If you’re not happy with those examples, let's look at Brazil.

Brazil

According to trade data, Brazil’s average applied tariff rate is approximately 13.5%. However, specific sectors face significantly higher rates, particularly the automotive industry, where the import tax on cars is set at 35%, with additional taxes that vary by engine size and fuel type. This high tariff, effective as of 2025, aims to protect domestic manufacturers like Fiat and Volkswagen, which have significant production facilities in Brazil.

Ownership laws for foreign companies in Brazil generally reportedly allow 100% foreign ownership, however, restrictions exist in certain sectors to protect national interests. For instance, in the media sector, radio and television stations must be majority-owned by Brazilian citizens, a policy rooted in cultural preservation and national security concerns. Additionally, sectors like financial institutions, telecommunications, and defense require prior approval for foreign investment, creating bureaucratic hurdles that can delay market entry.

Still not satisfied? No stress, I’ll give you a sixth example: Japan.

Japan

Japan’s protectionist policies are predominantly focused on agriculture, with high tariffs on sensitive products to shield domestic farmers from international competition. Research indicates Japan’s average applied tariff rate is around 2.5%, reflecting its integration into global trade networks. However, agricultural products face significantly higher tariffs, with rice being a prime example. The tariff on rice is set at a specific amount per kilogram, with a reported ad valorem equivalent of approximately 341%. This high tariff, effective in 2025, protects Japan’s rice farmers, a critical cultural and economic sector, but it also limits consumer access to cheaper imports.

Non-tariff barriers also play a significant role in Japan’s protectionism. For example, distribution networks also pose challenges, with keiretsu systems and long-standing relationships often giving domestic companies an advantage which means there’s no fair competition in the country as these keiretsu structured companies such as Mitsubishi, Toyota, and Sumitomo are essentially monopolies.

Now I’m far from an expert on trade policy, and the details of these tariffs and trade barriers may differ slightly if you dig deeper because I’ve only touched on a few examples in each of the countries I mentioned, but the fact remains that a number of different countries have tariffs and other trade barriers on imported goods.

So it makes no sense to label Donald Trump as delusional and misguided because everyone in the respective countries above can find an argument to support a narrative that their respective protectionist policies have been beneficial to their economies in some way. I encourage everyone to go look for the tariffs that their country has on imported goods–because your country has them too.

Another point that everyone seems to be missing is that it's important to be self sufficient. Need a certain good? No problem, my domestic neighbour has it. That drives productivity and output in the local economy and makes everyone in that economy better off. As a simplified economic cycle: higher productivity = higher incomes = higher spending = higher productivity = higher incomes, and so on.

What happens when the most powerful economy becomes self-sufficient? Many people have argued that the U.S. are bullies, well, imagine the unchecked power they’ll have once they don’t have to rely on another country at all. The thing we should really care about however, is whether our own countries are as self-sufficient, and if not, why not. Because self-sufficiency is in fact a national security issue.

2. Here’s why tariffs will not lead to higher prices in the long term…

Yes, if you’re in the U.S. and you normally import goods to sell to U.S. consumers, you’ll be worried about these tariffs. And yes, if the tariffs are effective from today, then your next order will probably cost a little more. But that’s not guaranteed because the cost factor is multifaceted.

In most cases, tariffs are partially offset by the exchange rate. If the U.S. dollar is appreciating then the cost of imports is cheaper, so the stronger dollar partially offsets the tariff imposed on that good. The producer will also take on part of the tariff cost as a cost of sale. Then the final consumer takes on a much smaller percentage of that tariff as a price increase. So to avoid tariffs; make in America!

Additionally, it's possible for the government to come in with policies that help domestic manufacturing for the tariffed goods. For example, in Trump's first round of tariffs in his first term, there was a 30% tax on foreign solar panels and modules imported into the United States. The tariff decreased by 5% each year until it bottomed out at 15%. Instead of rising, prices of solar panels in the U.S. actually fell, and continued their fall right through the tariff regime.

U.S. domestic manufacturing of solar panels increased.

And American manufacturing of solar panels was further supported by the Inflation Reduction Act which was introduced by the Biden administration. The solar tariff program worked so well that President Biden doubled the tariff from 25% to 50% last year in 2024 before he left office.

I got this example from a post from Anthony Pompliano, and you can read his letter to see more similar examples of how the first round of tariffs in the U.S. during Trump 1.0 didn’t cause inflation.

But that’s what Liberation Day is about. Liberation from unfair trade that the U.S. has been subject to, liberation from the lie that we’ve been told about how trade today is free trade, liberation from hypocrisy when countries say that the U.S. cannot have protectionist policies while implementing and enforcing tariffs and other protectionist policies in their own countries.

What’s Next From Here?

Already the 10Y U.S. treasury bond yield has come down to 4%, and is trending lower. But that could just mean that the markets believe that interest rates will be lower in the U.S. and not necessarily a reflection of market sentiment that the administration will succeed in its plans to reduce U.S. national debt, cut government spending, and reduce trade deficits while driving additional government revenue through tariffs. But time will tell.

Let’s also not forget that tariffs can and should be negotiated. After all, it's called trade, and trade is a negotiation. A lot of these tariffs I’m sure will stay for a while before the Trump administration entertains any negotiations. Trump has already brushed off the Vietnamese President when he tried to initiate negotiations a few days ago. Instead of humming along and relying on global trade practices introduced more than 40 years ago, we should all wake up and accept that the world is very different to what it looked like 40 or even 20 years ago. Countries like South Africa, and other developing economies, should try to really reason from first principles on the quality of industrial policies in the country and whether those policies are really effective. After 20 years of BEE policies in South Africa, is it working, and where can we improve? After 20 years of being the world’s manufacturer, can China sustain their low cost manufacturing business model or are they stuck in a middle income trap?

Right now, no mainstream publication is talking about the truth I’ve tried to dig into in this letter. Instead we’re seeing mainstream media try to push fear, uncertainty, and doubt which is mostly unfounded because 1) tariffs have never caused inflation in the United States as shown in the above examples and because they’ve never been implemented at this scale so how can you know, and 2) remember the media has never liked Trump so anything he does is bad in their minds. Imagine the horror of someone running for the Presidency, promising to fix the economy, getting elected by a landslide to do exactly that, and has been doing so since day one.

Change is uncomfortable so it's normal for all of these countries that were just hit with tariffs to be screaming in “pain”, but what we really should be doing is screaming at our own respective presidents to get their business hats on and do actual work to shape a productive industrial policy in the country.

On my journey to becoming a master capital allocator, one lesson down, a billion more to go.

Hope you all have a great day.

-Mansa

Share this post