To Investors,

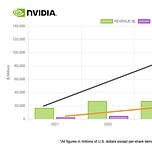

Last week, while looking at NVIDIA’s financials as well as listening to industry experts on NVIDIA and NVIDIA’s position in the AI space, I was made aware that NVIDIA’s accounts receivable has grown from $2.3 billion in 2021 to $26 billion in 2024. That's a 9.5x increase. In the same period, NVIDIA’s revenues went up 7.8x to $130 billion in FY 2025.

While it's normal for a company to have accounts receivables (AR), it's also important to keep on eye on that figure and to ensure that all measures possible are put in place so that that AR can be recognised as revenue not too far into the future. Also, one of the main reasons that any company has credit terms with any supplier is to optimise its cash conversion cycle. A longer accounts payable term means a shorter cash conversion cycle. But today we’re specifically noting the size increase in NVIDIA’s AR within a short space of time, and trying to make sense of why.

So, does NVIDIA have an accounts receivable problem? Maybe, but unlikely. Here's why…

For starters, NVIDIA has an approximately 90% market share of AI-specific GPUs and AI architecture. This dominance is driven by their superior products built specifically for AI workloads. You may have heard people talk about H100 and H200 GPUs, as well as the related networking infrastructure that allows companies to build supercomputers for AI training–well that's NVIDIA’s Hopper platform for AI. In late 2024 however, NVIDIA officially released a new platform called Blackwell which offers 30 times greater performance, at an energy consumption that's 25 times lower than Hopper. I asked Perplexity to create a table that shows a comparison between NVIDIA’s Hopper and Blackwell platforms:

I think there are two factors at play that are making NVIDIA’s accounts receivables grow significantly.

One factor at play is that every company in the world that thinks they should, is trying to get their hands on NVIDIA GPUs to build their own AI training infrastructure. xAI set a new standard for the amount of money it costs to build a supercomputer for AI training, that will provide a significant competitive edge. According to Grok “xAI's Colossus supercomputer, initially launched with 100,000 NVIDIA H100 GPUs in 2024, likely cost between $3 billion and $4 billion to establish, according to industry estimates. This figure encompasses the GPUs—priced at $25,000-$40,000 each—plus the extensive infrastructure, including a 750,000-square-foot data center in Memphis, advanced cooling systems, and a robust power setup with a $24 million substation.”

Doubled to 200,000 GPUs by December 2024, that's an additional $3 billion for the cost of GPUs alone, at an estimated $30 000 per unit.

The second factor at play is that there are very few companies that can afford to spend that type of money for an uncertain outcome. On top of just providing GPUs, NVIDIA offers computing solutions which include suggestions on the best architecture to build compute power, so it's fair to say that those customers that can, will negotiate a term where they only pay once the solution is up and running.

At the same time, towards the end of FY 2025 NVIDIA started shipping Blackwell, which led to “billions of dollars in sales” according to Jensen. That's a very new product, which we can assume was made available to certain customers before it was released publicly. The point is NVIDIA is constantly innovating, and if they want to get their expensive and unproven products into the market quickly, they’ll need to put together special terms that feed into accounts receivables with certain customers.

In a note in NVIDIA’s latest annual report the company mentions that “Two direct customers accounted for 17% and 16% of [NVIDIA’s] accounts receivable balance as of January 26, 2025. Two direct customers accounted for 24% and 11% of [NVIDIA’s] accounts receivable balance as of January 28, 2024”

So to allow a customer to buy on account the customer needs to have a great relationship with the seller, and the customer must also be creditworthy.

Who could these companies be that are responsible for a third of NVIDIA’s accounts receivables?

Grok suggested that we consider the following options, which are also NVIDIA partners in cloud services and data centres:

Distributors (e.g., Ingram Micro, Synnex/TD Synnex, or Arrow Electronics):

NVIDIA relies on distributors to sell its GPUs to smaller OEMs, system integrators, and retailers. Companies like Ingram Micro or TD Synnex are major players in the electronics distribution space and could account for significant receivable balances due to the volume of GeForce GPUs or data center products they handle.

OEMs/System Builders (e.g., Dell, HP, or Super Micro Computer):

Large OEMs integrate NVIDIA GPUs into their servers, workstations, and gaming PCs. Dell and HP, for example, are key partners for NVIDIA’s data center and professional visualisation products, while Super Micro Computer is a major player in AI and high-performance computing servers.

Hyperscale Cloud Providers (e.g., Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud):

NVIDIA’s data center business, driven by products like the A100 and H100 GPUs, caters to cloud giants building AI and machine learning infrastructure. These companies could represent substantial accounts receivable if they purchase directly from NVIDIA rather than through intermediaries.

Consumer Electronics Retailers or Partners (e.g., Best Buy, ASUS, MSI):

For the gaming segment (GeForce GPUs), NVIDIA sells to partners like ASUS or MSI (who produce graphics cards) or large retailers like Best Buy. These could be significant debtors, especially during high-demand periods like new product launches.

I added a fifth, which is that the companies driving up NVIDIA’s AR are repeat customers who’ve built goodwill, like xAI as Elon has built a relationship with NVIDIA over the years through Tesla. This would also make sense because xAI is a startup with little revenue, therefore through a bespoke contract they could be purchasing from NVIDIA on account.

The companies mentioned above are large and mostly financially stable businesses, which means 1) they can afford to negotiate a contract where they agree to buy NVIDIA’s products and solutions, and only pay once they prove the product can work as preferred, and 2) the companies are creditworthy.

So while you should keep an eye on NVIDIA’s accounts receivables as a capital allocator, you should also try to piece together the entire story–and that should help you determine whether NVIDIA has an accounts receivable problem or not. I’m still learning and I don’t know enough to definitively say whether there is a problem or not, but I would like to note that apparently NVIDIA has so much demand for their products that they are struggling to fulfil orders. A classic example is how Tesla decided to build their own GPUs for a Tesla specific cluster called Dojo because they felt NVIDIA couldn’t meet their demand.

The point is that NVIDIA doesn’t need to sell GPUs and other products on account to anyone. My guess is that NVIDIA wants to get their products out in the market as quickly as possible, especially if it's a new product like Blackwell, so NVIDIA is using every reasonable method to get there. One way to do that is to sell on account to credit worthy customers, and the other is to invest in the ecosystem so that there are customers to take on your products, but that second method is something I’ll discuss in another letter.

On my journey to becoming a master capital allocator, one lesson down, a billion more to go

Hope you all have a great day

-Mansa